Find out how pricing psychology offers a simple way to increase your product sales. Learn more about the 12 most common pricing psychology strategies.

Pricing psychology leverages the study of consumer behaviour to influence our every day buying decisions. By analysing how certain numbers, wording, and images associated with products resonate with consumers, companies can maximise their sales in a relatively pain-free way.

Whilst many well-known principles of pricing psychology may seem too simple and obvious to still be effective, in-depth academic research has proven that even the most straightforward techniques are continuing to have a significant impact on consumers’ purchasing decisions.

Here are 12 common pricing psychology strategies being used today that highlight its effects.

1. Charm pricing

Charm pricing is one of the most highly prevalent instances of pricing psychology and can be found at play in most transactional settings. It involves lowering a product’s left digit by one, and reducing its cost by one cent (e.g. $3.00 becomes $2.99), to make it a more appealing price to the customer.

People are more attracted to $2.99 than $3.00 as they isolate the left digit and associate it with the lower cost of $2.00, rather than its true value of nearly $3.00 (Asamoah and Chovancová 2011). It is suggested that buyers are inclined to round numbers down in their heads, rather than up when it comes to pricing.

2. Comparative pricing

When faced with a standard or premium option, customers are more likely to select the premium option if the price is framed as the cost of an upgrade to the standard option, rather than independently as a whole cost (Allard, Hardisty and Griffin 2016).

For example, consider a $999 smart watch placed beside its $1,099 counterpart, which has a larger screen and more storage. The customer is more likely to go for the latter option when it is framed as a $100 upgrade from the $999 option, rather than the full $1,099 if it were viewed on its own.

3. Prestige pricing

For certain products, lower prices don’t always equate to higher sales. Longer lasting purchases, customers are often motivated primarily by quality and customers tend to associate higher prices with better quality (Deshpande 2018).

Pricing products at a higher level to reflect luxury attracts those buyers who make the correlation between price and quality and will, therefore, justify paying the higher price.

4. Sales pricing display

The way a discounted offer is displayed potentially has a larger bearing on a customer’s potential to buy it than the value of the discount (Coulter & Coulter 2005); text font, colour, and size all play a major role in how customers receive sales messages.

This study and others have also suggested that displaying the discounted price in smaller text than the original price is more likely to lead to a purchase, as customers – whether consciously or not – make the connection that smaller text = smaller cost.

5. The decoy effect

Notably demonstrated by Dan Ariely’s The Economist example (2009), the decoy effect is a cognitive bias phenomenon dictating that customers are likely to change their purchasing decisions between two products when a third product (decoy) is offered. The decoy is a product which most people would not logically choose and influences customers to purchase a particular option from the original two – despite their original choice potentially being otherwise.

Ariely’s example sees The Economist offering three subscription options: $59 for Web Only, $125 for Print Only, and $125 for Web & Print; most customers opted for the Web & Print over the others as they were unable to determine the best value option with the decoy (Print Only) thrown into the mix.

6. Flash sales

Flash sales are characterised by mass demand and an influx of sales for retailers. Ramachandran (2017) explains that flash sales work so well because factors, such as time pressure, competitiveness, and limited quantities all place urgency upon customers.

This urgency results in less reasoning time and a higher likelihood to make purchases on a whim. The research also found that as these constraints are tightened, e.g. shorter times or fewer products available, the number of sales also rises.

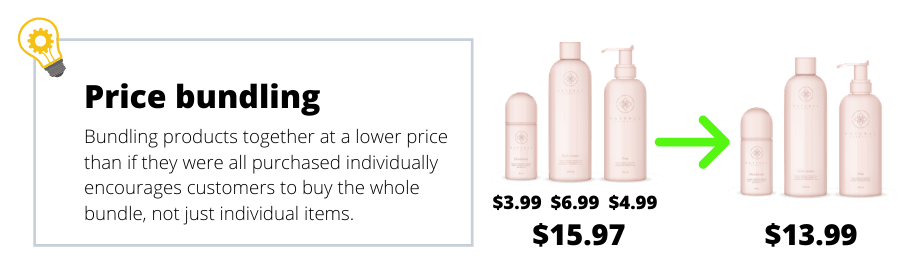

7. Price bundling

Price bundling is the practice of selling a group of products together at a lower price than the total combined price if they were to be purchased separately. This technique encourages higher spend from customers, as the prospect of an overall discount supersedes the additional cost of purchasing the bundle rather than just the single product they were after (Sett 2014).

Research also shows that price bundling disrupts customers’ ability to assess what they feel is a fair price for each product, making them more susceptible to make the bundle purchase. This technique also encourages repeat purchasing of several items from a brand’s product line instead of just the single item the customer was originally after.

8. Discount format

Displaying the same discount in an alternative format can affect how well it is received among customers. Wagner (2011) compares price promotions framed in percentage versus dollar value terms.

The study shows that customers will consume discounts differently depending on how they are numerically communicated. It found that consumers prefer to see a price reduction in dollar value when the item is in the higher price range, e.g. a mobile phone advertised as ‘$200 off’, whereas the opposite is true for lower-priced items, e.g. 25% off a stick of deodorant.

9. Zero price

Ariely, Mazar and Shampanier (2007) conducted several experiences to highlight the ‘zero price’ effect, which shows resounding evidence that lower transaction costs are not the sole motivating factor behind the offer of ‘free’ being so attractive to customers.

Through several experiments, the study demonstrates that customers will often choose from a variety of products based on which option has the highest cost-benefit difference. However, when items/offerings are free (zero price), customers use a different thought process and deem something that is free as having higher perceived benefits on top of decreased cost.

10. Slight price changes

Making slight pricing changes to similar products increases the ability for customers to choose between options and, in turn, make a purchase (Dhar, Kim and Novemsky 2012). The study asserts that when products are different prices, customers have an easier time recognising differences between them and identifying similarities, making the decision-making process faster and more likely to occur due to the less complicated means of deduction required.

Participants were asked to choose between two packets of gum priced $1.25 each, and then between the same packets at slightly different prices - $1.26 and $1.27. This theory held true as 77% of participants stated they would likely choose an option when presented with two different prices as opposed to only 46% when the same prices for each packet of gum were displayed.

11. Price anchoring

Price anchoring works off the premise that customers use relative pricing to make their decisions and as such, by establishing a pricing ‘anchor’ as a point of reference, can influence a buyer to pay for the most expensive option on offer. Poundstone (2011) explains that people don’t usually have a strong grasp in terms of what constitutes a reasonable price for a product, and instead shape their perceptions off indeterminate factors which are shaped by what is directly in front of them.

For example, consider a $999 watch is offered next to a $6,599 watch – the latter is clearly the better-quality option, but the customer may still struggle to justify the cost. Present a $6,999 watch on the side and the customer is not only more likely to go for the $6,599 option but also consider paying just an extra $400 for the most expensive watch; an easy sell for those who were originally considering the middle-priced watch.

12. Pricing order

Displaying a list of prices, e.g. a menu, in descending order can drive profit due to more customers choosing pricier options. Suk, Lee and Lichtenstein (2012) conducted an experiment in which beer prices were listed in differing orders, concluding that price lists in descending order are more likely to attract higher price points. An A/B test case study, featured on the go-to digital marketing resource, GuessTheTest, found anchoring prices from highest to lowest markedly increased sales of Internet plans for the telecommunications company, T-Mobile.

This is mostly due to the human phenomenon to fear what one may lose; when offered with more expensive options first, customers felt they would lose out on quality the further they scanned down the list – a thought process that would not occur had the prices been in ascending order.