Practical tips for setting up conjoint studies

The research team at Conjointly have supported clients in setting up numerous research projects that involve conjoint analysis, and has gained a whole of lot of experience along the way. In this guide, we share our most important learnings from past projects to make sure yours is a success. (You will find plenty of other recommendations on other pages too.)

Nine tips for specifying attributes and levels

Attributes are ‘dimensions’ of your product (such as price, colour, shape, size, brand, location):

Include the attributes that you believe are most important to your customers when they make buying decisions, as well as any attribute whose importance you would like to check. For example, if you know that customers are driven by price and size, and want to investigate whether colour is important, include all three attributes (price, size, and colour).

Try not to include more than seven attributes because it might confuse your respondents or may look too clunky, especially on mobile devices.

If price can be included (i.e. if you are testing a consumer good), generally price should be included as an attribute even if you are not interested in learning about its importance because:

It helps make the study more realistic.

It makes it possible to compare other attributes relative to price across several studies (for example, if you decide to run another study with a different set of attributes).

Levels are the ‘values’ that each attribute can take. For example, the attribute ‘colour’ can have levels ‘blue’, ‘red’, ‘transparent’. The attribute ‘features’ can be ‘no updates included’, ‘automatic update every month for one year’, ‘lifetime automatic updates’.

Keep in mind that you need to have at least two levels per attribute. If one of your attributes has only one level, include it as a characteristic in your product description.

Levels should be precise: e.g. the levels of the engine power of a car are 1.5L, 1.8L, 2.0L, not “less than 1.5L” or “more than 2L”.

Levels need to sound realistic to the consumer (but necessarily feasible for your production line at present).

Make sure the levels are mutually exclusive within each attribute. For example, consider textures of tissue paper. For this attribute, one may specify the levels “recycled” and “weave-like”. This is not mutually exclusive because recycled can be “weave-like”. This can be avoided by specifying two attributes:

Attribute “Texture”: “weave-like texture”, “simple texture”;

Attribute “Recycled”: “recycled”, “not recycled”.

For both attributes and levels:

When describing both attributes and levels, use the language that customers understand because in their screen they will see attributes and levels exactly as you describe them. Think of the kind of language you would use in customer-oriented advertising. You should ask your salespeople and marketing team to test your conjoint study for understandability before sending it out to customers or panel respondents.

A picture is worth a thousand words. Use images, especially if you have trouble describing your product features.

Five common mistakes in conjoint studies

Below, we collate five most common mistakes people make when setting up and interpreting a conjoint study – so that you can avoid them.

1. Testing too many features in a single conjoint experiment

Typically, consumers only focus on the most important features when making purchases, so it is not necessary to include all features of your product. Consider two factors:

The more features you add, the harder it is for respondents to compare each option in your conjoint study.

Your experiment’s complexity and sample size will increase with every feature you add, making your experiment more expensive without necessarily improving the reliability of your findings.

2. Exceeding the limits of what a single conjoint can handle

Similar to the mistake of adding too many features, including too many other inputs will also make the survey overly complex, increasing the sample size and cost. Points to consider:

Include up to 7 attributes with enough levels to be reflective of the market. You can also include additional questions, but keep these to a minimum to avoid respondent fatigue.

Price points should range from ~60% to 140% of the realistic price. If you are unsure of the realistic price, conduct a Van Westendorp study to narrow it down.

Ask a moderate number of conjoint questions (between 10-14). Having more than 14 questions can cause respondent fatigue. The automatic default on Conjointly is around 12 (depending on your set-up).

3. Not distinguishing between features clearly enough

Respondents can often get confused about features when one feature is a combination of several parameters. For example, if a promo offer is included in the total price, respondents may get confused if the additional promotional price parameter is not clearly identified.

This confusion can also arise among products with technical variations. For example, laundry detergent is available in several similar varieties (e.g. liquid and concentrate). To clearly differentiate between each substance and make a fair comparison, respondents would need the specific characteristics of each explained to them.

How to avoid it:

Product features should be clearly distinct.

Adding additional information for each attribute can clear any potential confusion.

Add intro pages of your features before the conjoint.

4. Relying exclusively on average utility scores

Conjoint studies provide rich datasets of individual respondents’ preferences for the levels tested. Looking exclusively at high-level average scores prevents you from taking full advantage of this data. You should always play with simulations in addition to average utility scores for fuller understanding of consumers’ preferences.

5. Not adjusting preference shares for market conditions

One of the great things about doing conjoint analysis is that it approximates market shares based on customers’ preferences. But remember: conjoint-based market share simulation should not be relied on in isolation as it is nearly impossible to:

- include every competitor’s offering in the market,

- predict changes in consumer behaviour and future product launches by competitors,

- perfectly factor in shelf availability of products,

- assume that the finished product on the shelf will be exactly as what you test in conjoint.

Should you include competition in your research?

If your study is about pricing, then you definitely should include competitors in your conjoint. To illustrate this, let us take a look at two examples:

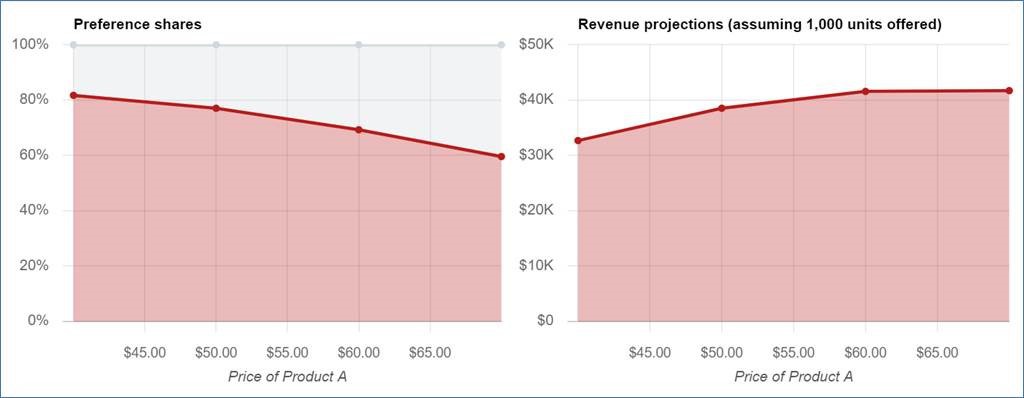

Without competition

In the analysis below, there was only one product in conjoint, meaning respondents had choice of either Product A (red area) or “None of the above” (i.e. not buy product A). This is typically an unrealistic situation because respondents typically have several choices in the marketplace. As a result, the elasticity charts tends to be flat and it underestimates price elasticity:

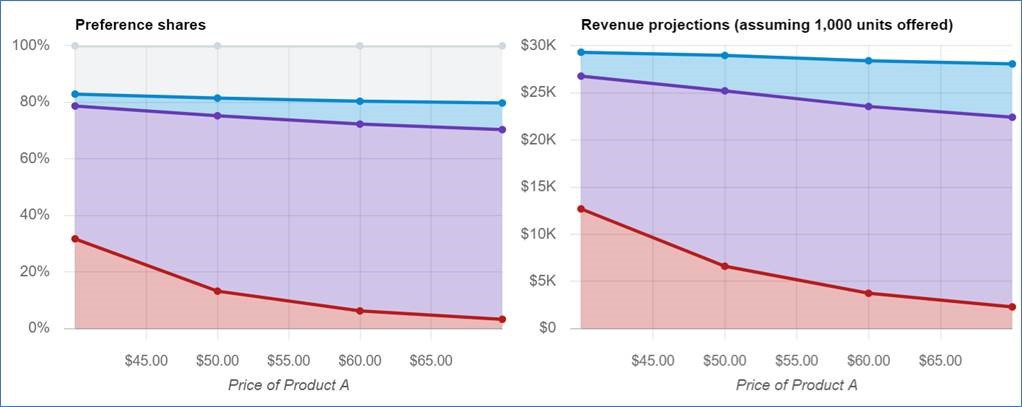

With competition

For comparison, below is analysis of the same product A (in red) with some competitor options included. As you can see results are quite different, almost opposite.

This second option is much more realistic because in reality consumers have more choices to consider and make their purchase decision out of the available options.

In essence pricing research is about asking the question “if you offer product X at price $y, what % of people will be willing to buy it?”. By testing in a competitive context (i.e. including competition), we make the study more realistic as we allow consumers to switch brands when another brand is simulated at a higher price.

Sample definition for pricing research

When you do pricing research, it is especially important to have representative sample of category buyers, with quotas by household income and brand usage (gender and age are less relevant, but can be useful for balancing the sample).

If you oversample buyers of specific brands, you risk underestimating price elasticity of demand for those brands.

Should you include 5 SKUs or 12 SKUs in a conjoint?

Choice modelling (conjoint analysis, both standard and virtual shelf) typically makes the assumption of independence of irrelevant as alternatives, which means that the number of inferior SKUs offered in a set with a superior SKU will not affect people’s choice: whether there are 4 or 11 inferior SKUs in addition to the superior SKU.

Broadly speaking, these are the factors to consider when deciding how many SKUs to include:

Consideration for including 12 SKUs (virtual shelf display)

- Because for every choice set we record one chosen choice, having a larger set of offerings has the benefit of better discerning the top option

- An exercise of 12 SKUs is more realistic in terms of the number of SKUs offered (typically you have closer to a dozen SKUs as options rather than 5)

Consideration for including 5 SKUs (standard conjoint)

- Helps to recognise close second options (which can be the winning option if the top option is excluded), this is often harder when we have a larger choice set.

Special considerations for consumer goods

For those who work in already established CPG/FMCG markets, we have some special reminders:

As a rule of thumb for studies where pricing or range optimisation are the key objectives (and where simulations will be main outputs), you should include SKUs that makes up to ~80% of the market. Doing so will require some balancing and in our experience we have found that one should include SKUs that represent:

- Top SKUs by sales,

- Most salient brands (e.g., prominent newcomers to the market),

- Variants of your product you are keen to understand market’s reaction to,

- Your most direct and comparable competitors (in terms of pack size, price level, key features),

- At least one or two competitor SKUs in each of the key size group (e.g. in small, medium, and large),

- At least one or two competitor SKUs in each at each value/price level (e.g. budget, mid-tier, premium).

Ideally, think of the items (and their attributes and levels) that will be sold two or three months from now, not what is on the market today.

When you think of price, always think of size as well. In some markets you also need to show price per pack or price per 100g. Conditional display logic can assist you with that.

Include an opt-out option (i.e. none of the above) as the consumer might not want to take any of the options in real-life. This is absolutely necessary for pricing.

Use the Conjointly image optimisation tool to make sure that:

- Images are sized proportionally to pack size.

- Images are of consistent quality, especially for mobiles devices.

Do not place more than 5 alternatives per screen (choice task). Generally, virtual shelf display with dozens of SKUs shown at once is not essential as we have not seen any evidence in academic literature or in practice that virtual shelf display predicts market outcomes better than simple conjoint, however, it is more costly and laborious.

What every market research project should have

Finally, we have some thoughts that apply across all online research studies:

Include some profiling questions to learn more about the demographics of your customers: e.g., age, income, education level. Conjointly lets you analyse these as well.

Include open-ends. Even if you do not want to hear what your customers want to tell you in an open-ended format, they are a great way to identify and remove low-quality respondents.

Pre-test your survey with a handful of respondents (your colleagues or Quick Feedback) to ensure the survey fulfills the objectives of your investigation.